Sharpening an Old Saw

By Kenneth Turner Blackshaw

When is the last time you saw an owl? I remember as a child, marveling at the Snowy Owl under its glass dome in my Grandpa Turner's den. It was ten years later, I encountered my first of these ghostly birds near the end of Smith's Point, when you could still ride your bike out there. But the owl we're discussing this week is much smaller and stealthier -- a bird I didn't actually see.

Slowly the sound oozed into my mind. It wasn't loud, but insistent, repeating over and over again, almost twice a second -- a whistled "toooooot - tooooot - toooooot". We were at the platform tennis courts off the Polpis Road, and just gathering our duds after a good bash. I said to my friend Sheddon, "You hear that?" "Hear what?" he says. "That whistle." I said. And then Sheddon heard it too, slowly growing louder.

This was the voice of Eastern North America's smallest Owl, a bird named for his call -- the Saw-whet Owl. Nowadays we don't hear saws being sharpened much, but people tell me this is what one would sound like.

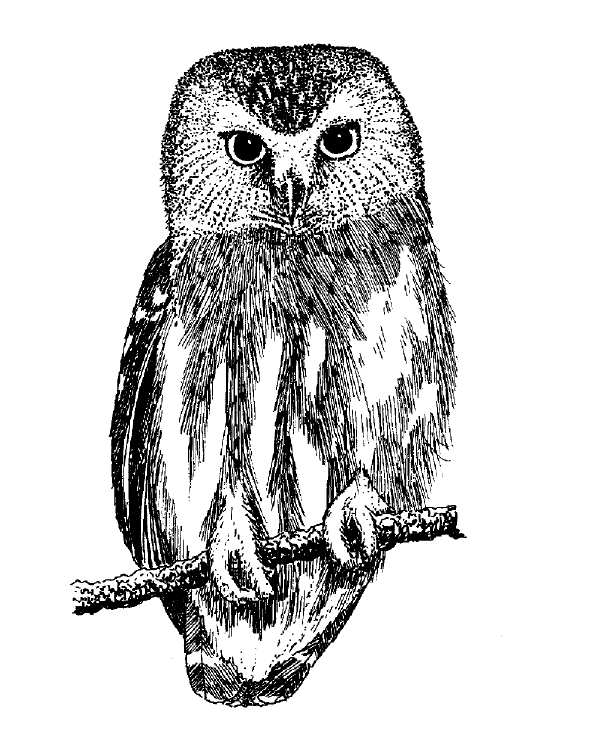

These owls are very small, measuring eight inches from beak to tail, a half-inch smaller than a starling. Of course owls have huge heads in comparison to the rest of the body, and the beak really doesn't stick out like a starling's. Saw-whets are mainly brown with bold vertical streaks in front. Their huge yellow eyes dominate their appearance.

"Birding Nantucket" lists this species as being uncommon year 'round and nesting from April to June. Actually it's been a while since they were found nesting in the State Pines, but these birds are so secretive that we can assume they are nesting somewhere. Their typical spot is an abandoned large woodpecker hole, perhaps a Northern Flicker's. The ones in the State Pines actually used a birdbox, and we still check that box when we walk through the pines.

"Birding Nantucket" lists this species as being uncommon year 'round and nesting from April to June. Actually it's been a while since they were found nesting in the State Pines, but these birds are so secretive that we can assume they are nesting somewhere. Their typical spot is an abandoned large woodpecker hole, perhaps a Northern Flicker's. The ones in the State Pines actually used a birdbox, and we still check that box when we walk through the pines.

The 1948 "Birds of Nantucket" only lists two records for this tiny owl, both back in the 1920's. But this is a bird that lives over the whole of North America from Alaska to New Brunswick, so it was probably around historically as well -- just hiding.

When you see an owl, you mainly notice the head, with both eyes staring to the front. This gives them a vaguely human-like appearance and is the reason that we hear about "wise old owls". This is another myth, since owls are seldom old and rank rather low in wisdom in the bird world. However, having both eyes forward gives them excellent binocular vision and great depth perception which helps with hunting.

However, forward-facing eyes provide very poor side vision. Therefor owls spend a lot of time swiveling their heads around in order to see things not directly in front of them. Legend says they can turn their heads a full 360 degrees -- again, not true. But they can go past 180, and the rapid switch from backwards, all the way around the other way approaches that phenomenon.

Saw-whets subsist almost completely on mice, a prey almost as large as they are. These they generally swallow whole -- a rather amazing process. Their digestive system is such that they can separate the good, from the bad, from the truly ugly, so to speak. Then, the bad and ugly are regurgitated in the form of a pellet. When we look for owls, we look for 'whitewash' on a tree from the droppings, and then under the tree we look for pellets. Scientists enjoy taking pellets apart so they can see what the owls have been eating. They are surprisingly clean and not offending to humans, so you can separate fur and bones. I've heard them referred to as 'do-it-yourself' mouse kits. All you need are the instructions!

Once in Colorado when we were studying Great Horned Owls, I picked up a pellet and was industriously digging through it, finding bits of bone, but it seemed different somehow. My friend commented, "You've picked up a coyote feces, Ken." Not one of my better days!

We have a surprising number of Saw-whet Owls in our collection at the Maria Mitchell Association. Considering how shy these little owls are, you wouldn't think we would find them dead. But their habit of 'hawking' for moths along the roadways causes too many of them to be hit by cars. So, they are often found dead on the road and make their way to our collection. One of Edith Andrews' favorites is a 'hatch-year' bird, still with his buffy brown tummy and white face, a bird that undoubtedly hatched here on Nantucket.

For the next few weeks, our Saw-whet Owls are reinforced by migratory ones that pass through on their way farther north. If you are out at dusk, listen for the repetitive whistled tooting they make. It is easy to mimic this, and these birds are very curious. You can have an up close and personal experience with these little owls -- a very precious experience you will long remember.

George C. West creates illustrations for these articles.

If you enjoy social birding, every Sunday a group meets in the parking lot in front of the Nantucket High School at 8 a.m.

To hear about rare birds, or to leave a bird report call the Massachusetts Audubon hot line at 888-224-6444, option 4.

"Birding Nantucket" lists this species as being uncommon year 'round and nesting from April to June. Actually it's been a while since they were found nesting in the State Pines, but these birds are so secretive that we can assume they are nesting somewhere. Their typical spot is an abandoned large woodpecker hole, perhaps a Northern Flicker's. The ones in the State Pines actually used a birdbox, and we still check that box when we walk through the pines.

"Birding Nantucket" lists this species as being uncommon year 'round and nesting from April to June. Actually it's been a while since they were found nesting in the State Pines, but these birds are so secretive that we can assume they are nesting somewhere. Their typical spot is an abandoned large woodpecker hole, perhaps a Northern Flicker's. The ones in the State Pines actually used a birdbox, and we still check that box when we walk through the pines.